Research Article - (2025) Volume 4, Issue 2

“Everyone has it and it’s not just you”: How Eleven to Thirteen Year Olds Perceive Anxiety

Received Date: Mar 01, 2025 / Accepted Date: Mar 26, 2025 / Published Date: Mar 31, 2025

Copyright: �??�?�©2025 Eva Luke. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Citation: Luke, E. (2025). â??Everyone has it and itâ??s not just youâ?: How Eleven to Thirteen Year Olds Perceive Anxiety. Int J Clin Med Edu Res, 4(2), 01-09.

Abstract

Dooley et al showed that over 30% of Irish adolescents experienced levels of depression and anxiety outside of a normal range [1]. While their research was conducted on secondary school students, eleven to thirteen year old students make up the early adolescent years. There is a great deal of research on anxiety disorders, but few which listen to the young person’s own voice, particularly during these early adolescent years. While the Children’s School Lives study shows research on anxiety for children, questions did not leave room for children to speak about their understanding of anxiety, or speak openly on what they believe may cause feelings of anxiety. Furthermore, Roose and John found that 10 and 11 year olds were cognitively able to discuss the concept of mental health [2]. This study hopes to address this gap in knowledge and see what students' understanding and experiences of anxiety are, further demonstrating that research should be done with, rather than on, children particularly when considering mental health [3]. Main findings suggest many children have an understanding of anxiety, with most participants having heard the term before and were able to give examples of when it may be experienced. Children had many ideas on how to lessen anxiety for themselves and their peers and what they believe schools should be doing to help with this. Main sources of anxiety that were identified for fifth and sixth class students were sports, tests, homework and the transition to secondary school.

Keywords

Anxiety, Mental Health, Adolescents, Young People, Understanding, Sources

Introduction

Globally, one in seven individuals between the ages of 10 and 19 experience a mental health disorder, which accounts for 13% of the global burden of disease for this age group [4]. However, these remain largely unrecognised, untreated, and understudied. It is estimated that 3.6% of 10 to 14 year-olds experience an anxiety disorder, making them the most prevalent mental health disorder for this age range, with girls being more likely to experience a disorder than boys [4,5]. Anxiety disorders in children rarely occur in isolation and are often highly comorbid with other anxiety and depressive disorders.

Anxiety has a purpose; to alert a person to a new potentially threatening scenario, which in the context of a child’s life, includes specific life events such as the first day of school [6]. While anxiety can be a natural response, high levels can signal an anxiety disorder. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders - 4th Edition (DSM-IV) outlines nine anxiety disorders for children; Separation Anxiety Disorder (SAD), Panic Disorder, Agoraphobia, Generalised Anxiety Disorder (GAD), Social Phobia, Specific Phobia, Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD), Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and Acute Stress Disorder [7]. The focus of a child’s anxiety is how these are diagnosed.

There have been longitudinal declines in the mental health of adolescents, particularly among girls, when comparing pre- pandemic to intra-pandemic levels [8]. O’Sullivan et al report that half of all mental health disorders develop before the age of 14 [9]. Children who have an anxiety disorder are at a much greater risk of continuing to experience an anxiety disorder through adolescence and early adulthood. Poor mental health has shown associations with teenage pregnancy, road traffic accidents, crime and suicide [10]. High levels of anxiety in children are linked to a child’s avoidance of school, peer activities, parental relationships, poor self-esteem, and lower academic achievement [5,6]. Childhood anxiety disorders represent a serious health issue and pose an increased risk of psychiatric disorders during adulthood [11]. Whether having a diagnosed disorder, or just experiencing symptoms of anxiety, anxiety can significantly interfere with children’s interpersonal and academic abilities. It has been predicted by Duchesne et al (cited in MagelinskaitÄ? et al) that high anxiety in primary school predicted non-completion of high school [12]. ‘Children’s School Lives’, an in-depth study into Irish primary school students’ experiences, highlighted how anxiety was connected to a sense of failure [13]. Higher school- based anxiety was also linked to lower learning motivation [12].

Referrals to the Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) in Ireland, have increased in recent years, putting CAMHS under unprecedented pressure to care for children and young people at risk [14]. Studies agreed that most youth who met criteria for having a mental illness were not receiving professional help and fewer yet had contact with CAMHS. Schools offer great potential to promote positive health and wellbeing from an early age as they can target many children at once [15]. However, curriculum overload and insufficient training were mentioned by teachers as barriers to implementing wellbeing policies and initiatives. Teachers felt more funding, Continuous Professional Development (CPD) and resources were needed to implement such policies or initiatives [15]. After reviewing 38 studies on mental health interventions, Das et al,found that group-based interventions and Cognitive Behavioural Therapy were successful in reducing depressive symptoms and anxiety [10]. Corrieri et al similarly found that 73% of interventions studied were effective in reducing anxiety [16].

Due to gaps in current research, particularly from children’s own voices, the objectives of this study are:

• to understand how children view anxiety

• to determine what children’s experiences of anxiety are

• to reveal what adolescents believe their sources of anxiety are The potential implications of this study are to influence teachers' understanding of what they can do to lessen and help children with anxiety, and to better understand the supports needed by children when experiencing perceptions of anxiety. These shared perceptions by children regarding their experiences with anxiety and desired supports will provide implications for future research, policies and practice for mental health and wellbeing in education.

Method

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee for the Masters in Adolescent Health Programme in the University of Galway. Written consent and assent forms from the parents and children were required before research began.

School Background and Recruitment

The school used for the research is a large, non-DEIS (Delivering Equality of Opportunity in Schools) school located in South Dublin under the patronage of the Catholic Archbishop of Dublin.

The study was introduced and access negotiated with the Board of Management, who manage the school on behalf of the patron. Once access was granted, the study commenced in Spring of 2024. This direct communication ensures positive relationships between the gatekeepers and researchers [17].

Participant Recruitment

Schools do not generally allow contact details for parents to be given to researchers [18]. Therefore, the most common method of contacting parents is through students. In Ireland, children in the final terms of fifth and sixth classes in primary school are typically between the ages of 11 and 13. Therefore, four fifth class and sixth class teachers were asked for permission to conduct the study with their classes. They agreed, and the study was introduced to their classes with each student being given an information packet. These information packets contained letters of consent and assent, general information about the study and its purpose, as well my own contact information should parents have any questions about the study. Children’s participation in research requires a parent or guardian’s consent and a child’s assent. In this regard, once parental consent is acquired, the child provides their own assent to participate in the study [19]. Informed consent and assent were essential so that participants were fully aware of the purpose of the research [20]. Students were made aware that their participation was voluntary, pseudonyms would be used to ensure anonymity, that the school would not be identified and that they had the right to leave the study at any time.

Inclusion Criteria

To be included in the research a child had to be in the sample school, between the ages of eleven and thirteen, in one of the four sample classes and return consent and assent forms by the deadline of April 12th.

Focus Group Selection

Of the four classes, 24 students returned all completed forms and volunteered to participate (18 girls and 6 boys). Table 1 below demonstrates the number of participants, including their pseudonyms, ethnicity, age, sex and class level and which focus group they participated in. Four focus groups were made, including an all-boys group, a sixth class girls group and two fifth class groups. An all-boys focus group was formed as research has shown that in focus groups with children, girls can appear withdrawn in group discussions and allow boys to lead conversations [21]. Over the course of three months from April to June, each group was met three times to ensure saturation of the data by drawing out participant perspectives through multiple discussions. Table 2 summarises each focus group’s attendance. An interview schedule was created and shared with the school principal before each focus group occurred (see Appendix I), ensuring questions were appropriate for the study. All sessions were semi-structured to explore participant perspectives and were all audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim (see Appendix II).

|

Pseudonym |

Sex |

Ethnicity |

Age at first focus group |

Class Level |

Focus Group No. |

|

Henry |

Male |

White Irish |

11 |

5th |

1 |

|

Kevo |

Male |

White Irish |

11 |

5th |

1 |

|

Michael |

Male |

White Irish |

11 |

5th |

1 |

|

Apollo |

Male |

White Irish |

11 |

5th |

1 |

|

Patrick |

Male |

White Irish |

11 |

5th |

1 |

|

John |

Male |

White Irish |

13 |

6th |

1 |

|

Olivia |

Female |

White Irish |

12 |

6th |

2 |

|

Ella |

Female |

White Irish |

13 |

6th |

2 |

|

Julia |

Female |

White Irish |

12 |

6th |

2 |

|

Zoe |

Female |

White Irish |

12 |

6th |

2 |

|

Rachel |

Female |

White Irish |

12 |

6th |

2 |

|

Audrey |

Female |

Chinese |

12 |

6th |

2 |

|

Taylor |

Female |

White Irish |

12 |

6th |

2 |

|

Michelle |

Female |

White Irish |

12 |

6th |

2 |

|

Grace |

Female |

White Irish |

11 |

5th |

3 |

|

Catherine |

Female |

White Irish |

11 |

5th |

3 |

|

Stacey |

Female |

White Irish |

11 |

5th |

3 |

|

Jenny |

Female |

Indian |

11 |

5th |

3 |

|

Lisa |

Female |

White Irish |

11 |

5th |

3 |

|

Marta |

Female |

White Irish |

11 |

5th |

4 |

|

Katie |

Female |

White Irish |

11 |

5th |

4 |

|

Maddie |

Female |

White Irish |

11 |

5th |

4 |

|

Holly |

Female |

White Irish |

11 |

5th |

4 |

|

Daisy |

Female |

White Irish |

11 |

5th |

4 |

Table 1: Summary of All Participants

|

Focus Group: |

Session 1 attendance: |

Session 2 attendance: |

Session 3 attendance: |

|

1. Boys Group (5th/6th Class) |

6 |

5 |

5 |

|

2. 6th Class Girls |

8 |

7 |

8 |

|

3. 5th Class Girls |

5 |

4 |

5 |

|

4. 5th Class Girls |

5 |

4 |

4 |

Table 2: Focus Group Attendance

Data Collection

Traditionally, children’s lives were explored primarily through the views and understanding of their parents and guardians [3]. This excluded the child from the research process. Focus groups are viewed as being well suited for researching the views of children [22,23]. Indeed, focus groups enable child participants to be spontaneous, view the research as fun, and offer a safe environment for children, thus allowing them to speak freely [23]. Furthermore, Horner reports that children between the ages of 11 to 14 are more hesitant when talking to adult strangers, but more relaxed when among a group of peers [21].

Focus groups generally involve a small number of participants engaging in a discussion with a moderator in a structured interview manner [24]. Friendship-based focus groups allow children’s perspectives to be shared in as natural a setting as possible [25]. For groups 3 and 4, the participants were all known to each other, for group 1 they were from two classes next door to each other, and for group 2, the all-boys group, participants were from three different classes. Focus groups should be participant friendly rather than just child friendly as they can fit into everyday routines, which proved particularly true with this research as the focus groups were during a regular school day, meaning there was no change to the children’s daily school schedule [3]. The setting for the focus groups should be familiar and comfortable to students; a classroom is related to work and a strict hierarchy [21,22]. For this reason, focus groups took place in the school library, viewed as a favourable place for students in the school.

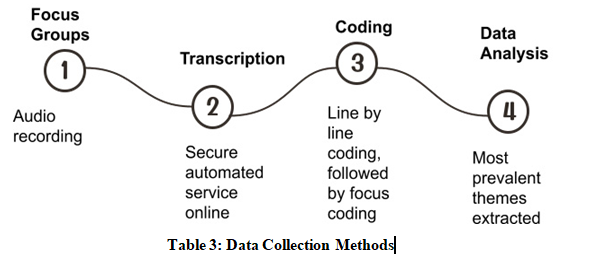

Table 3 below shows the order in which the data was collected, starting with the audio recording of each focus group. Some of the questions asked included; “What do you think the word anxiety means?” in the first focus group, “Do you think it’s normal for children your age to have anxiety?” in the second focus group and “How has it felt talking about anxiety in a group?” in the final focus group. These audio recordings were then transcribed by a secure automated service, underwent initial line-by-line and focused coding, with the most prevalent responses and patterns being drawn out.

Data Analysis

Transcriptions were completed using a secure automated service online. This was done after each focus group and reviewed at length for accuracy. Coding of the research began once all focus groups were complete. Research was conducted using the Constructivist Grounded Theory [26]. During the coding process, this allows researchers to use simultaneous data collection and analysis which informs and focuses the next stage of research [26]. In this case, codes from transcripts helped create the next interview schedule. Line by line coding, where transcripts were analysed and each line assigned to a theme, was followed by focus coding, to identify the most prevalent themes and significant data that were arising. The focus coding allowed room to show the intensity of comments made which is important for the data analysis process of the research [27]. The key patterns that arose regarding sources of anxiety for students were based on homework, tests, the transition to secondary school and P.E..

Results

The twelve group discussions gave insight into the participants' understanding of anxiety, their experiences of it and their perceived sources of anxiety. Children also spoke proactively on their opinions of how anxiety is talked about, what they believe would benefit them regarding anxiety, and their overall opinions on the group discussion. Direct quotes are included in these sections, but all names listed are pseudonyms to ensure anonymity.

Children’s Understanding of Anxiety

During focus group discussions, children shared their perceptions regarding the definition of anxiety. Students understood anxiety as being nervous, stressed, worried and overthinking, as shown in Table 4.

|

Definition |

Student |

|

Anxiety is when you get scared or nervous about something that is “Big for you, but wouldn’t be as big for some people” |

Patrick |

|

“Worried at its max” |

Michael |

|

“Worrying over things that aren’t as big a deal as you think” |

Olivia |

|

“When you’re worried about something that might happen in the future or something that’s happening” |

Stacey |

|

“A sense of nervousness that can be really extreme sometimes” |

Grace |

Table 4: Students’ Definitions of Anxiety

While some children felt that they already understood anxiety, others felt that they learned a lot from talking about it with each other during the focus group discussions. Additionally, children disagreed on whether most children understood anxiety or not, with some believing that most have some level of understanding, while others stated that most children don’t understand it at all.

Children’s Experiences of Anxiety

Most children perceived that they have more experiences of anxiety presently than when they were younger. Children attributed this to knowing more about what’s going on in the world, having more responsibilities and more pressure placed on them (e.g., from parents, coaches, teachers). Children’s perceptions varied in believing whether or not it’s normal for children to have feelings of anxiety. Here, some children stated that most children do have experiences of anxiety, while others said some level of anxiety is normal, and others perceived experiences of anxiety to not be normal at this age. Many children felt that they don’t hear anxiety spoken about much, but reported that, while limited, anxiety has been heard in common places such as books, television shows, movies, and in class.

Reported responses to feelings of anxiety varied, including biting nails, feeling sick and finding it hard to concentrate on anything else. Children mentioned that some people try to hide their anxiety, with some girls feeling that boys in particular do this, stating that it may be because boys think it’s not ‘cool’ to show anxiety.

Sources of Anxiety

There were many different sources of anxiety identified by students. The four most prevalent sources, or themes, were homework, tests, the transition to secondary school and sports or P. E, (Table 5).

“[Homework] is just boring and it’s just like stressful sometimes because if I don’t get it all done then it’s like yeah there’s like a lot to do and you don’t have enough time” (Katie)

“I, I get anxious sometimes during the Drumcondra test because like I find there’s always like a timer kind of on you like an hour or something and I feel like I’m not gonna get it done on time” (Maddie)

“...Sometimes I just think about like, what if I went to the other one [secondary school] and I like, and then I get stressed about like, oh, what if I don’t make any friends in this new one because I don’t know anybody” (Rachel)

“I’m anxious about losing, letting my team down, that sort of stuff” (Kevo)

|

Theme |

Summary of key items within the theme |

|

Homework |

|

|

Tests |

|

|

Transition to Secondary School |

|

|

Sports/P.E. |

|

Table 5: Summary of Themes for Sources of Anxiety

Other sources of anxiety brought up by more than one student were walking home alone, reading aloud in front of peers, being late, pressure to have the latest things and how others think you look. Social media or being online was not named as a source of anxiety by children in this study.

Children’s Opinions on Anxiety

Children generally believed that anxiety should be talked about more. However, the level to this varied, with some stating that talking about it too much may cause more anxiety. Others felt that the more anxiety is talked about the more normalised it will become, which will help children dealing with anxiety feel less embarrassed to bring it up.

“Everyone has it [anxiety] and it’s not just you” (Stacey)

“[Anxiety] will eventually go away if you talk to somebody” (Patrick).

Suggested Solutions

Children felt strongly that anxiety is not talked about enough in school, with some mentioning the need for a safe space in the school for students to talk. Children felt that a room in the school accessible to all students, similar to a sensory room, would be beneficial.

“[It would be] good to have a safe space to be able to talk about your feelings without anybody judging you” (John).

Others felt like the Social, Personal and Health Education (SPHE) Curriculum should include more on anxiety, with some feeling like there should be a dedicated teacher available to talk about it with. Students mentioned that they may not feel as comfortable talking about some of the sources of anxiety (e.g. homework and tests) with their own class teacher but another teacher who is available would be preferred.

Conversations on Anxiety

Overall, children perceived focus group discussions about anxiety to be a positive experience. Many students mentioned how great it felt to ‘let it all out’, feeling like a weight was lifted off their shoulders. Others spoke positively about how glad they were to hear they are not alone in their feelings and how it felt like a safe space to share.

“... it kind of feels like I’ve lifted a weight off my shoulders of like the burden of being worried about secondary school…” (Michelle)

Discussion

As the findings have shown, the data presented here indicates that 11 to 13 year olds have a good understanding of what anxiety is and when it may be experienced by children their age, including during homework completion, taking tests, moving to secondary school and during sports. Participants reported that homework is a key driver for anxiety amongst their peers. In a study by Holland et al, 37% of parents reported that their child feels stress or anxiety towards homework [28]. Interestingly, not one teacher in this study reported during preliminary and follow-up conversations that homework negatively affects the social and emotional wellbeing of their students. Therefore, the disconnect between teacher and student perceptions establishes a need for teachers to understand the anxiety that homework brings.

Tests are perceived as a major source of concern for many children, with test anxiety becoming more prevalent with the increased role tests play in education [29,30]. Indeed, students in this study also commented on the anxiety that tests bring due to worries of failing and letting people down. As students progress through the more senior classes in primary school, the anxiety that testing, particularly standardised testing, provokes within children is more significant [13]. The transition to secondary school is known to be a time of potential vulnerability for children [31]. While transition involves both academic and social challenges, children also mentioned concerns about the curriculum becoming more difficult [32]. Children in this study spoke strongly on their anxieties regarding moving to second-level education, particularly 6th class students. Indeed, O’Brien argues that this; “transfer is an emotional time, a time of concern and loss” [33]..â½p.264â¾ Participants spoke about many causes for their anxiety, including moving schools, but placed stronger emphasis on anxiety caused by friendships, as children are shown to be most concerned with personal and social issues during the transition to secondary school [34]. Indeed, it is proven to be important for a 13 year old to have established social connections prior to starting a new school to support social integration [35,36].

These findings align with perceptions shared by children in this study, as they expressed the importance of having friends in school and included concerns over not knowing anyone in their future secondary school. While Lucey and Reay argued that a majority of anxiety around these educational transitions comes from the presence of potential bullying, concerns about bullying were not mentioned by any participant in this study [37]. While studies suggest that sport and physical activity can act as a protective factor for young people’s mental health, including a reported link shown between high physical activity and reduced anxiety, the participants in this research stated that team sports are a source of anxiety for them, showing that sport can simultaneously be both a protective and risk factor for anxiety [38-40].

It is important to note here that neither social media or internet usage were ever identified by the children in this study as a source of anxiety. These perspectives therefore demonstrate the importance of researching with children, and subsequently learning from their perspectives, particularly in order to understand the accurate relevance of different sources of anxiety for children. This contrast between assumed sources of anxiety, and children’s reported sources of anxiety further highlights that children hold a status as experts on their own lives and should be at the forefront of future research [22]. As these findings both contribute to existing literature and provide unique findings, there are vital implications for future research, policy, and practice for supporting children through

feelings of anxiety. Future research on children’s experiences and perceptions of anxiety should be conducted on a larger scale from more demographics, over the course of a full school year to better identify sources of anxiety and the levels to which they are identified. Additionally, National Wellbeing policies from the Department of Education should recognise from these findings that children want to speak about mental health more, benefit from having a safe space to talk about mental health, and strongly feel that mental health should be taught explicitly in the classroom.

Implications & Contribution Statement

This research intends to enable those conducting future research and developing policies in the area of education and mental health for adolescents to better understand the supports needed by children when experiencing anxiety and to influence teachers' understanding of what they can do to lessen and help children with anxiety.

Conclusion

Most students understand anxiety to a degree. They hear about it in places such as books, television shows, and in the classroom. This study highlights the importance of researching with children to learn from their perspectives in order to understand the accurate relevance of different sources of anxiety for children. Eleven to thirteen year old students believe the main sources of anxiety in their lives are homework, tests, the transition to secondary school and sports or P.E. The reasoning for these includes students feeling that their lives are too busy for the amount of homework received, and feeling pressure to perform well for tests, stemming from a worry about letting parents and teachers down. In addition, students face a great deal of anxiety in the transition to secondary school for many reasons such as making new friends, old friendships drifting and the curriculum becoming more difficult. Results from this study have shown that children want to have a safe space to talk about anxiety and mental health and felt that they benefited from speaking about mental health.

Limitations

Although this research emphasised and drew findings from the child’s perspective, it is difficult to know if the children in this study agreed with each other to please their peers during focus group discussions. On the other hand, the use of focus groups facilitated a comfortable interview space and can be argued as vital to this research. There were three times more girls who volunteered to partake, showing gender inequality with perspectives. Furthermore, this research was very short-term and focus groups were conducted from April to June. Standardised tests occur in this school in May every year, so this could have influenced the children’s view of testing being a key source of anxiety. Absence rates are generally higher in the final term of the school year, and so not all 24 students were present for the final two focus groups. The timing of the focus groups may also have been important for the identification of the transition to secondary school being a source of anxiety, as it was only a few months away for those in sixth class.

References

1. Albano, A. M., Chorpita, B. F., & Barlow, D. H. (2003). Childhood anxiety disorders. Child psychopathology, 2, 279- 329.

2. Al-Sheyab, N. A., Alomari, M. A., Khabour, O. F., Shattnawi, K. K., & Alzoubi, K. H. (2019). Assent and consent in pediatric and adolescent research: school children’s perspectives. Adolescent Health, Medicine and Therapeutics, 7-14.

3. Alves, J. M., Yunker, A. G., DeFendis, A., Xiang, A. H., & Page, K. A. (2021). BMI status and associations between affect, physical activity and anxiety among US children during COVIDâ?ÂÂ19. Pediatric obesity, 16(9), e12786.

4. American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed.

5. Barrett, P., & Turner, C. (2001). Prevention of anxiety symptoms in primary school children: Preliminary results from a universal schoolâ?ÂÂbased trial. British journal of clinical psychology, 40(4), 399-410.

6. Bourke, R., & Loveridge, J. (2014). Exploring informed consent and dissent through children's participation in educational research. International Journal of Research & Method in Education, 37(2), 151-165.

7. Breen, R. L. (2006). A practical guide to focus-group research. Journal of geography in higher education, 30(3), 463-475.

8. Charmaz, K. (2005). Grounded Theory in the 21st Century: Application for Advancing Social Justice Studies. In: Denzin, N.K. and Lincoln, Y.S., Eds., The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research, 3rd Edition, Sage Publications, London, 507-535.

9. Christensen PM, James, A. (2017). Research with Children: Perspectives and Practices. Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

10. Corrieri, S., Heider, D., Conrad, I., Blume, A., König, H. H., & Riedel-Heller, S. G. (2014). School-based prevention programs for depression and anxiety in adolescence: A systematic review. Health promotion international, 29(3), 427-441.

11. Das, J. K., Salam, R. A., Lassi, Z. S., Khan, M. N., Mahmood, W., Patel, V., & Bhutta, Z. A. (2016). Interventions for adolescent mental health: an overview of systematic reviews. Journal of adolescent health, 59(4), S49-S60.

12. Dooley, B., Fitzgerald, A., & Giollabhui, N. M. (2015). The risk and protective factors associated with depression and anxiety in a national sample of Irish adolescents. Irish Journal of Psychological Medicine, 32(1), 93-105.

13. Headley, C., Campbell, M. (2013). Teachers’ knowledge of anxiety and identification of excessive anxiety in children. Aust J Teach Educ, 38(5).

14. Higgins, E., & Booker, R. (2022). The implementation of a whole school approach to mental health and well-being promotion in the Irish primary school context. Health Education Journal, 81(6), 649-666.

15. Holland, M., Courtney, M., Vergara, J., McIntyre, D., Nix, S., Marion, A., & Shergill, G. (2021, August). Homework and children in grades 3–6: Purpose, policy and non-academic impact. In Child & Youth Care Forum (Vol. 50, pp. 631-651). Springer US.

16. Horner, S. D. (2000). Using focus group methods with middle school children. Research in nursing & health, 23(6), 510- 517.

17. Jago, R., Brockman, R., Fox, K. R., Cartwright, K., Page, A. S., & Thompson, J. L. (2009). Friendship groups and physical activity: qualitative findings on how physical activity is initiated and maintained among 10–11 year old children. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 6, 1-9.

18. Jindal-Snape, D., & Miller, D. J. (2008). A challenge of living? Understanding the psycho-social processes of the child during primary-secondary transition through resilience and self-esteem theories. Educational Psychology Review, 20, 217-236.

19. Jones, C. D., Newsome, J., Levin, K., Wilmot, A., McNulty, J. A., & Kline, T. (2018). Friends or strangers? A feasibility study of an innovative focus group methodology. The Qualitative Report, 23(1), 98-112.

20. Lucey, H., & Reay, D. (2000). Identities in transition: Anxiety and excitement in the move to secondary school. Oxford Review of Education, 26(2), 191-205.

21. Lynch, S., McDonnell, T., Leahy, D., Gavin, B., & McNicholas, F. (2023). Prevalence of mental health disorders in children and adolescents in the Republic of Ireland: a systematic review. Irish journal of psychological medicine, 40(1), 51-62.

22. MacRuairc, G. (2011). They’re my words–I’ll talk how I like! Examining social class and linguistic practice among primary- school children. Language and Education, 25(6), 535-559.

23. MagelinskaitÃÂ??, Š., KepalaitÃÂ??, A., & Legkauskas, V. (2014). Relationship between social competence, learning motivation, and school anxiety in primary school. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 116, 2936-2940.

24. Magson, N. R., Freeman, J. Y., Rapee, R. M., Richardson, C. E., Oar, E. L., & Fardouly, J. (2021). Risk and protective factors for prospective changes in adolescent mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of youth and adolescence, 50, 44-57.

25. Martinez Sainz, G., Devine, D., Sloan, S., Symonds, J., Ioannidou, O., Moore, B., ... & Gilligan, E. (2023). Curriculum and Assessment in Children's School Lives: Experiences from Primary Schools in Ireland 2019–2023 (No. Children’s School Lives). University College Dublin.

26. McDonald, A. S. (2001). The prevalence and effects of test anxiety in school children. Educational psychology, 21(1), 89- 101.

27. Oates, C., & Riaz, N. N. (2016). Accessing the field: methodological difficulties of research in schools. Education in the North, 23(2), 53-74.

28. O’Brien, M. (2003). Girls and Transition to Second-level Schooling in Ireland: “Moving on” and “moving out”. Gend Educ, 15(3), 249-267.

29. O’Sullivan, K., Clark, S., McGrane, A., Rock, N., Burke, L., Boyle, N., ... & Marshall, K. (2021). A qualitative study of child and adolescent mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic in Ireland. International journal of environmental research and public health, 18(3), 1062.

30. Pluhar, E., McCracken, C., Griffith, K. L., Christino, M. A., Sugimoto, D., & Meehan III, W. P. (2019). Team sport athletes may be less likely to suffer anxiety or depression than individual sport athletes. Journal of sports science & medicine, 18(3), 490.

31. Roose, G.A., & John,A. M. (2003).A focus group investigation into young children's understanding of mental health and their views on appropriate services for their age group. Child: care, health and development, 29(6), 545-550.

32. Dimech, A. S., & Seiler, R. (2011). Extra-curricular sport participation: A potential buffer against social anxiety symptoms in primary school children. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 12(4), 347-354.

33. Smyth, E. (2016). Social relationships and the transition to secondary education. The Economic and Social Review, 47(4, Winter), 451-476.

34. Smyth, E., & Privalko, I. (2024). School transition difficulty in Scotland and Ireland: a longitudinal perspective. Educational Review, 76(7), 1825-1841.

35. Visser, T., Ringoot, A., Arends, L., Luijk, M., & Severiens, S. (2023). What do students need to support their transition to secondary school?. Educational Research, 65(3), 320-336.

36. Vogl, S., Schmidt, E. M., & Kapella, O. (2023). Focus groups with children: Practicalities and methodological insights. In Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research (Vol. 24, No. 2). DEU.

37. Von der Embse, N., Barterian, J., & Segool, N. (2013). Test anxiety interventions for children and adolescents:Asystematic review of treatment studies from 2000–2010. Psychology in the Schools, 50(1), 57-71.

38. Williams, J., Thornton, M., Morgan, M., et al. (2018). Growing up in Ireland: The Lives of 13-Year-Olds. Stationery Office.

39. Wolfenden, L., Kypri, K., Freund, M., & Hodder, R. (2009). Obtaining active parental consent for schoolâ?ÂÂbased research: a guide for researchers. Australian and New Zealand journal of public health, 33(3), 270-275.

40. World Health Organization. (2021). Mental health of adolescents. World Health Organization.